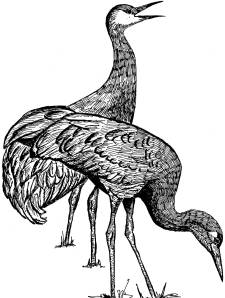

Greater Sandhill Cranes. Photo courtesy of Abby Jensen, www.jensen-photography.com.

Published Oct. 9, 2016, in the Wyoming Tribune Eagle: “Cranes are a “gateway bird”

[Yampa Valley Crane Festival story begins with snow]

By Barb Gorges

I visited the Yampa Valley Crane Festival in Steamboat Springs, Colorado, with my husband, Mark, in early September.

Steamboat is known for world-class skiing, but how does that relate to the festival centered around the greater sandhill crane?

It starts with a couple of skiers. Nancy Merrill, a native of Chicago, and her husband started skiing Steamboat in the late ’80s. They became fulltime residents by 2001.

Merrill was already “birdy,” as she describes it, by that point. She was even a member of the International Crane Foundation, an organization headquartered in Baraboo, Wisconsin, only three hours from Chicago.

She and her husband wanted to do something for birds in general when they moved to Colorado. They consulted with The Nature Conservancy to see if there was any property TNC would like them to buy and put into a conservation easement. As it turns out, there was a ranch next door to TNC’s own Carpenter Ranch property, on the Yampa River.

The previous owner left behind a list of birds seen on the property, but it wasn’t until she moved in that Merrill discovered the amount of crane activity, previously unknown, including cranes spending the night in that stretch of the river during migration stop overs—which we observed during the festival.

Cheyenne folks are more familiar with the other subspecies, the lesser sandhill crane, which funnels through central Nebraska in March. It winters in southwestern U.S. and Mexico and breeds in Alaska and Siberia. It averages 41 inches tall.

Greater sandhill cranes, by contrast, stand 46 inches tall, winter in southern New Mexico and breed in the Rockies, including Colorado, and on up through western Wyoming to British Columbia. Many come through the Yampa Valley in the fall, fattening up on waste grain in the fields for a few weeks.

In 2012 there was a proposal for a limited crane hunting season in Colorado. Only 14 states, including Wyoming, have seasons. The lack of hunting in 36 states could be due to the cranes’ charisma and their almost human characteristics in the way they live in family groups for 10 months after hatching their young. Mates stick together year after year, performing elaborate courtship dances.

Plus, they are slow to reproduce and we have memories of their dramatic population decline in the early 20th century.

Merrill and her friends from the Steamboat birding club were not going to let hunting happen if they could help it. Organized as the Colorado Crane Conservation Coalition, they were successful and decided to continue with educating people about the cranes.

Out of the blue, Merrill got a call from George Archibald, founder of the International Crane Foundation, congratulating the CCCC on their work and offering to come and speak, thus instigating the first Yampa Valley Crane Festival in 2012.

Merrill became an ICF board member and consequently has developed contacts resulting in many interesting speakers over the festival’s five years thus far. This year included Nyambayar Batbayar, director of the Wildlife Science and Conservation Center of Mongolia and an associate of ICF, and Barry Hartup, ICF veterinarian for whooping cranes.

Festival participants are maybe 40 percent local and 60 percent from out of the valley, from as far away as British Columbia. Merrill said they advertised in Bird Watchers Digest, a national magazine, and through Colorado Public Radio.

It is a small, friendly festival, with a mission to educate. The talks, held at the public library, are all free. A minimal amount charged for taking a shuttle bus at sunrise to see the cranes insures people will show up. [Eighty people thought rising early was worthwhile Friday morning alone.]

This year’s activities for children were wildly successful, from learning to call like a crane to a visit from Heather Henson, Jim Henson’s daughter, who has designed a wonderful, larger-than-life whooping crane puppet.

There was also a wine and cheese reception at a local gallery featuring crane art and a barbecue put on by the Routt County Cattlewomen. Life-size wooden cut-outs of cranes decorated by local artists were auctioned off.

We opted for the nature hike on Thunderhead Mountain at the Steamboat ski area. Gondola passes good for the whole day had been donated. This was just an example of how the crane festival benefits from a wide variety of supporters providing in-kind services and grants. Steamboat Springs is well-organized for tourism and luckily, crane viewing is best during the shoulder season, between general summer tourism and ski season.

Meanwhile, the CCCC has a new goal. Over the years, grain farming has dropped off, providing less waste grain for cranes. Now farmers and landowners are being encouraged financially to plant for the big birds. It means agriculture, cranes and tourism are supporting each other.

Merrill thinks of the cranes as an ambassador species, gateway to becoming concerned about nature, “The cranes do the work for us, we just harness them.”